What impact does social media, like Twitter, have on us?

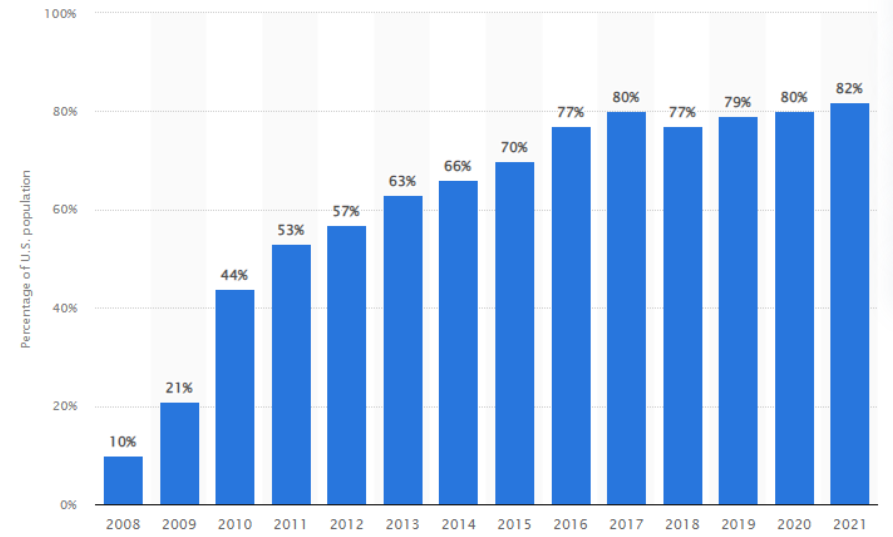

For many active social media users, our relationship with these platforms is complicated. The general sentiment toward social media changed gradually from optimism in the mid-2000s to mounting skepticism over the past few years. Pew Research Center found in 2020 that 64% of Americans believe social media delivers mostly a negative effect. And yet, 82% of Americans — and growing — use social media, according to Statista.

Social media users are caught in a love-hate relationship. On one hand, we find some value in our favorite platforms in the form of entertainment, relationships, education, or business. On the other hand, many people feel addicted to or exploited by social media.

We love keeping up with friends. But we’re tired of doomscrolling.

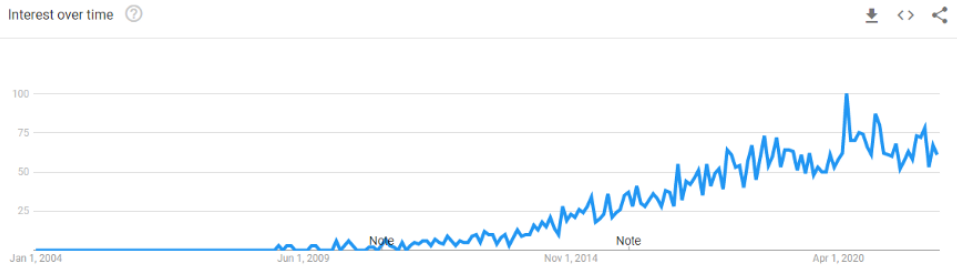

Many people are finding ways to self-regulate their social media usage through web blockers or social media fasts. Google search trends for the phrase “social media break” match almost perfectly with the growth of social media adoption. Both trended upward until 2017, and then sideways ever since.

But individual users aren’t the only ones wrestling with their relationship to social media. Governments have entered the social media conversation to determine the best way (if any) to regulate platform giants like Facebook.

Organizations, also, are reweighing the pros and cons of social media usage among their teams. On April 7, a leaked memo from inside The New York Times detailed the organization’s changing stance on Twitter usage for journalists. For several years, Twitter was a major resource for The New York Times reporters to connect with sources, share stories, follow growing trends, and generally grow brand awareness for the publication.

But according to the memo, those benefits have also come with a cost.

3 points from The New York Times memo

If maintaining an active presence on Twitter wasn’t required for New York Times reporters, it might as well have been. At least, that’s what we can infer from the contents of the memo, which was written by New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet. As Baquet wrote, “It’s clear we need to reset our stance on Twitter for the newsroom. So we’re making some changes.”

Baquet points to several reasons for The New York Times’ changing stance on Twitter: reporter harassment online, specific requests from journalists to get off (or spend less time on) Twitter, and journalist echo chambers (where reporters write for the social recognition of their colleagues).

To handle these drawbacks, Baquet detailed three changes:

- Twitter is now optional for The New York Times journalists.

- The New York Times will take greater action to protect journalists from online harassment.

- Journalists must follow stricter social media guidelines that adhere to The New York Times brand.

What does this mean under the surface?

Baquet’s memo is brief. Some additional context might surface new insights about this about-face from The New York Times. First, others have already speculated that this memo was sparked by a statement made by former New York Times columnist Bari Weiss.

Weiss wrote in her resignation letter: “Twitter is not on the masthead of The New York Times. But Twitter has become its ultimate editor. As the ethics and mores of that platform have become those of the paper, the paper itself has increasingly become a kind of performance space.”

Weiss was suggesting that The New York Times reporters are stuck in a Twitter echo chamber, where favorites and retweets matter more than objective journalism. Since Twitter is a popular social media channel for reporters, it’s easy to see why some have been accused of simply writing for the public recognition of their colleagues.

Another point of context to consider is the growth of personal writing brands on Twitter. Great reporting is arguably the most powerful marketing engine for most top-tier magazines. Speaking from my own experience, I have subscribed to both The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal simply to read the regular ideas and reporting of my favorite writers. Individual contributors play an enormous role in drawing readership to their publications.

The problem for magazines in the age of Twitter is that readers can now access the ideas of their favorite writers without necessarily subscribing to the publications.

Social media platforms like Twitter have allowed journalists to build personal brands. Think of it this way: When reporters are encouraged by their editors to pour ample time and energy into Twitter, the reporters are essentially being paid to grow their personal reputation and brand. What’s to stop the most popular reporters from simply moving away from magazines altogether to launch one-person media brands?

The short answer is: nothing.

A growing number of talented writers are leaving popular magazines to start paid newsletters. As the Wall Street Journal reported:

“The current boom in newsletters is creating new opportunities for some high-profile journalists to capitalize on their personal brands, potentially earn more income and get greater editorial autonomy than they typically enjoy. Services like Bulletin and Substack can make it easier for writers with followings to distribute and monetize their own newsletters.”

Could the pursuit of greater exclusivity be another reason The New York Times has suddenly pivoted its stance on Twitter? We can only speculate.

Will this memo change how journalists use Twitter?

Baquet did not outright condemn Twitter usage for journalists. The benefits of Twitter are still clearly present. But in his memo, it’s clear that Baquet sees major drawbacks to the overuse of this platform.

This begs many questions: Will The New York Times journalists maintain their same level of Twitter engagement, or steadily pull back? Will other publications follow in Baquet’s footsteps to discourage Twitter’s over-reliance on reporting?

Today, there are more questions than answers. As Baquet wrote, “This is a complicated topic, and our views [about Twitter usage] have evolved considerably over the last several years. I’m sure they’ll continue to.”

Alexander Lewis is a SaaS copywriter and executive ghostwriter in Austin, Texas. In his spare time, he publishes a free newsletter about the craft and business of writing.